Energy Expenditure and Adaptive Responses in Intermittent Fasting Trials

Resting Energy Expenditure During Intermittent Fasting

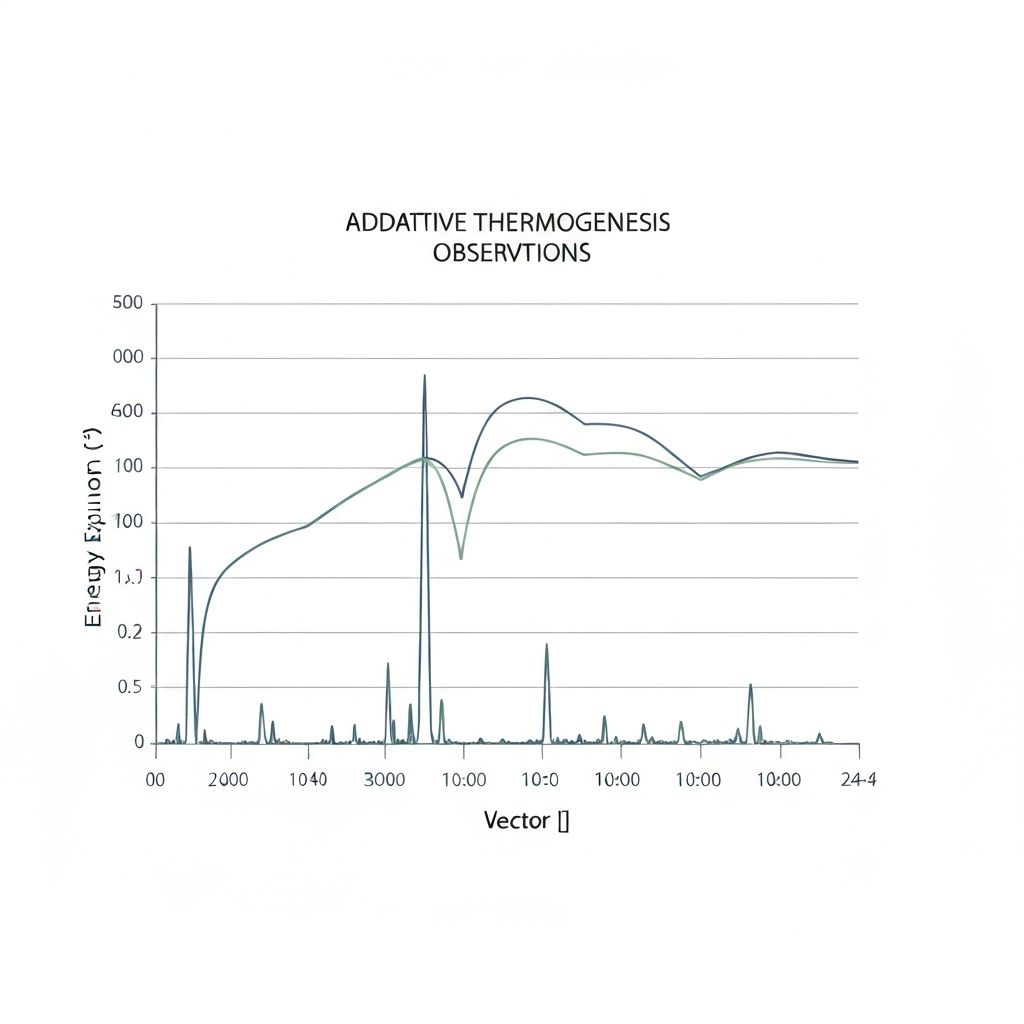

Energy expenditure—the rate at which the body utilises energy—represents a critical component of energy balance and body weight regulation. This article examines research findings on resting energy expenditure (REE) and adaptive thermogenesis during intermittent fasting protocols, presented for educational understanding of how metabolic rate responds to different eating patterns.

Components of Total Daily Energy Expenditure

Total daily energy expenditure comprises three primary components:

- Resting Energy Expenditure (REE): Energy utilised during rest to maintain basic physiological function (approximately 60–75% of total expenditure in sedentary individuals).

- Thermic Effect of Food (TEF): Energy required for digestion, absorption, and processing of consumed food (approximately 10% of total expenditure).

- Activity Energy Expenditure (AEE): Energy expended during intentional exercise and non-exercise movement (approximately 15–30% of total expenditure depending on activity level).

Short-Term Metabolic Rate Effects (First 24–48 Hours)

Initial Elevation Phase: During the initial transition into a fasting period, particularly during novel fasting experiences, sympathetic nervous system activation and elevated catecholamine levels produce modest increases in metabolic rate. Research indicates increases of approximately 3–10% above baseline during the first day of fasting.

Thermogenic Mechanisms: This initial metabolic elevation results from several mechanisms: increased catecholamine-mediated heat production, increased protein synthesis (in response to elevated amino acid ratios), and elevated growth hormone levels promoting lipolysis.

Clinical Significance: The magnitude of initial REE elevation is relatively modest and insufficient to substantially offset the energy deficit created by reduced food intake. A 5% REE increase in an individual with baseline REE of 1,600 kilocalories/day yields only 80 additional kilocalories of expenditure.

Metabolic Adaptation and Caloric Restriction

Adaptive Thermogenesis: During prolonged or repeated caloric deficit, metabolic rate typically declines below predicted values—a phenomenon termed adaptive thermogenesis or metabolic adaptation. This adaptation conserves energy in response to perceived scarcity.

Mechanisms of Adaptation: Metabolic adaptation involves multiple mechanisms: reduced sympathetic nervous system activity, decreased thyroid hormone levels (particularly T3, the active form), reductions in spontaneous physical activity, and alterations in energy allocation toward non-essential functions.

Magnitude of Adaptation: The degree of metabolic adaptation varies substantially but typically ranges from 10–25% reduction below predicted metabolic rate in response to significant caloric deficit. Larger deficits produce greater adaptive responses.

Intermittent Fasting vs. Continuous Restriction: Metabolic Rate Comparison

Research Findings: Controlled trials comparing intermittent fasting protocols (16:8, 5:2, ADF) to continuous caloric restriction reveal similar changes in resting energy expenditure when total weekly energy deficit is matched. This finding suggests that the pattern of eating (distributed vs. time-restricted) does not inherently prevent metabolic adaptation.

Study Design Limitations: Most published research examining metabolic rate during intermittent fasting involves relatively short durations (4–12 weeks). Longer-term studies are limited, making conclusions about long-term metabolic effects provisional.

Practical Implication: Both intermittent fasting and continuous caloric restriction result in similar metabolic rate reductions during sustained energy deficit. Metabolic adaptation is not prevented by eating pattern choice alone but rather depends on the magnitude of energy deficit and its duration.

Thermic Effect of Food During Intermittent Fasting

Definition: The thermic effect of food (TEF, also called postprandial thermogenesis) represents energy expended during digestion, absorption, and nutrient processing. TEF typically accounts for 8–15% of total daily energy expenditure.

Intermittent Fasting Impact: During the fasting period in time-restricted eating, TEF is absent or minimal (no food intake). During feeding windows, TEF occurs in response to consumed food. Some research suggests that compressed eating windows (fewer, larger meals) may produce higher per-meal thermic responses compared to distributed eating patterns, though total daily TEF remains similar when total caloric intake is matched.

Nutrient Composition Effect: Macronutrient composition influences TEF magnitude, with protein producing higher thermic effects (20–30% of protein energy) compared to carbohydrate (5–10%) and fat (0–3%). Individual meal composition during eating windows affects post-meal energy expenditure.

Activity Energy Expenditure Considerations

Exercise Timing: Individuals practicing intermittent fasting must consider exercise timing relative to fasting windows. Fasted exercise may influence performance, substrate utilisation, and recovery depending on training goals and individual response.

Non-Exercise Activity: Adaptive thermogenesis during caloric restriction includes reductions in spontaneous physical activity (fidgeting, postural changes, occupational movement). This reduction occurs independent of eating pattern and contributes substantially to metabolic adaptation.

Resistance Training Consideration: Individuals performing resistance training during energy deficit should prioritise adequate protein intake and total energy balance to support recovery. Exercise timing relative to fasting windows should optimise individual performance and recovery.

Individual Variation in Metabolic Adaptation

Baseline Factors: Initial metabolic rate, body composition (lean mass vs. fat mass), and genetic factors influence the magnitude of metabolic adaptation. Individuals with higher baseline metabolic rates may experience different adaptation patterns compared to those with lower baseline rates.

Age and Sex: Some research suggests age-related differences in metabolic adaptation, with older individuals potentially experiencing greater metabolic decline during caloric restriction. Sex-based differences in metabolic adaptation remain incompletely characterised.

Training Status: Individuals with high resistance training experience may exhibit different metabolic adaptation patterns compared to sedentary individuals, particularly regarding lean mass preservation during energy deficit.

Prior Dieting History: Individuals with extensive prior caloric restriction exposure may show accelerated or magnified metabolic adaptation, a phenomenon termed "metabolic memory" or the "repeated-bout effect."

Long-Term Metabolic Outcome

Weight Loss Plateau: During the first 1–2 months of caloric deficit (via either intermittent fasting or continuous restriction), weight loss typically progresses at a relatively steady rate. As metabolic adaptation develops and body weight declines, weight loss rate typically slows progressively.

Sustainability Implications: The slowing of weight loss as metabolic adaptation develops may reduce motivation for protocol continuation. Long-term adherence challenges affect both intermittent fasting and continuous restriction equally.

Recovery Upon Refeeding: When energy intake returns to maintenance levels after prolonged deficit, metabolic rate gradually recovers toward predicted values. However, recovery timing varies based on deficit severity and duration.

Explore Further

Learn about how appetite hormones respond to fasting and feeding patterns, and how individual factors influence responses to intermittent fasting protocols.

Return to articles